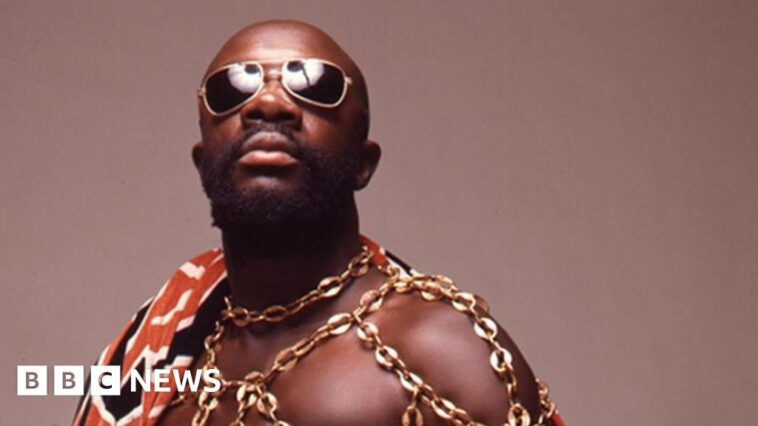

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe household of the late soul singer Isaac Hayes has ordered Donald Trump to cease taking part in the star’s music Hold On, I’m Coming at his marketing campaign rallies.

A letter despatched to Trump and his group, and shared by Hayes’ son on social media, threatens to sue the previous US President if he doesn’t comply by 16 August.

The household can be demanding $3m (£2.4m) in licensing charges for the marketing campaign’s repeated use of the music between 2022 and 2024.

The music, which was made well-known by soul duo Sam and Dave, is an everyday characteristic of Trump’s rallies, typically taking part in earlier than and after his speeches.

Hayes composed the music in 1966 with Dave Porter, when he was a workers author at Stax Records. He went on to turn out to be a Grammy and Oscar-winner in his personal proper, with hits like Shaft and Walk On By.

In their authorized letter, Hayes’ household claimed to have “asked repeatedly” for Trump to cease utilizing the music. They go on to quote 134 events on which the marketing campaign went forward anyway.

Their lawyer, James Walker, alleged that the Trump marketing campaign has “wilfully and brazenly engaged in copyright infringement”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe went on to demand that the campaign remove any videos featuring the song, and issue a full statement acknowledging that Hayes’ family have not “authorised, endorsed or permitted” the use of his music.

Walker added that the requested $3m settlement is a “closely discounted” figure, due to the frequency with which the campaign has played Hold On, I’m Coming.

The letter also stated that if a resolution was not made and a lawsuit was issued, the Hayes family would demand damages of $150,000 per use of the song – amounting to more than $20m (£15.7m).

The Trump campaign has yet to respond to the letter or the threat of legal action.

The Hayes family previously criticised Trump for playing Hold On, I’m Coming at a National Rifle Association convention, less than a week after the Uvalde school shooting in 2022, which claimed the lives of 19 people.

“Our condolences exit to the victims and households of Uvalde and mass taking pictures victims in all places,” they wrote at the time.

Porter, the song’s co-writer, also wrote: “I didn’t and wouldn’t approve of them utilizing the music for any of his functions.”

Meanwhile, Sam Porter – who sang the original hit recording – objected to Barack Obama using the song in his 2008 presidential campaign.

“I’ve not agreed to endorse you for the very best workplace in our land,” he said in a statement at the time.

“My vote is a really non-public matter between myself and the poll field,” he added.

Artist protests multiply

On Sunday, Hayes’ son, Isaac Hayes III, elaborated on his objections to the Trump campaign.

“Donald Trump epitomises an absence of integrity and sophistication, not solely by means of his steady use of my father’s music with out permission but in addition by means of his historical past of sexual abuse towards ladies and his racist rhetoric,” he wrote on Instagram.

“This behaviour will now not be tolerated, and we’ll take swift motion to place an finish to it.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Hayes family are the latest in a long line of musicians to complain about the Trump campaign.

The Beatles, Neil Young, Adele, Bruce Springsteen, Sinead O’Connor and Aerosmith are among the artists who have issued the politician with cease-and-desist orders.

In fact, the list of artists who have protested is so lengthy that the topic has its own Wikipedia page.

On Saturday, Celine Dion’s team also protested against the use of her track My Heart Will Go On at a rally in Montana.

“In no method is that this use authorised, and Celine Dion doesn’t endorse this or any comparable use,” a statement read.

“And actually, THAT music?”, it added – alluding to the fact that the track was recorded for the film Titanic, about a sinking ship.

However, musicians have only had limited success in stopping politicians from using their music.

In the US, campaigns are required to obtain a Political Entities License from the music rights body BMI, which gives them access to more than 20 million tracks for use in their rallies.

Artists and publishers can ask for their music to be withdrawn from the list, but it seems that organisers rarely check the database to ensure they have clearance.

“They don’t care as much about artists’ rights as perhaps you’d want,” said Larry Iser, a lawyer who represented Jackson Browne when he sued Republican candidate John McCain for one of his songs in a 2008 commercial. (The case was later settled).

“It’s not simply the Trump marketing campaign,” Iser told Billboard magazine. “Most political campaigns aren’t eager about simply taking the music down.”

Cases rarely, if ever, head to court – with both sides typically backing down after a flurry of legal letters.