Getty Images

Getty ImagesWe’re within the midst of a Moon rush. A rising variety of nations and firms have the lunar floor of their sights in a race for sources and area dominance. So are we prepared for this new period of lunar exploration?

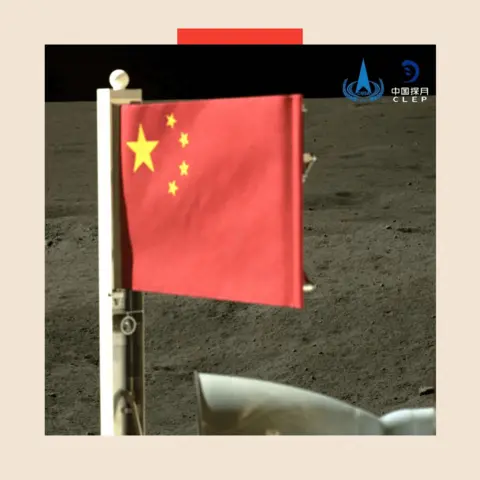

This week, photos have been beamed again to Earth of China’s flag unfurled on the Moon. It’s the nation’s fourth touchdown there – and the primary ever mission to return samples from the Moon’s far facet. In the previous 12 months, India and Japan have additionally set down spacecraft on the lunar floor. In February, US agency Intuitive Machines grew to become the primary non-public firm to place a lander on the Moon, and there are loads extra set to observe.

Meanwhile, Nasa desires to ship people again to the Moon, with its Artemis astronauts aiming for a 2026 touchdown. China says it’s going to ship people to the Moon by 2030. And as a substitute of fleeting visits, the plan is to construct everlasting bases.

But in an age of renewed great-power politics, this new area race may result in tensions on Earth being exported to the lunar floor.

“Our relationship with the Moon is going to fundamentally change very soon,” warns Justin Holcomb, a geologist from the University of Kansas. The rapidity of area exploration is now “outpacing our laws”, he says.

A UN settlement from 1967 says no nation can personal the Moon. Instead, the fantastically named Outer Space Treaty says it belongs to everybody, and that any exploration needs to be carried out for the good thing about all humankind and within the pursuits of all nations.

While it sounds very peaceable and collaborative – and it’s – the driving power behind the Outer Space Treaty wasn’t cooperation, however the politics of the Cold War.

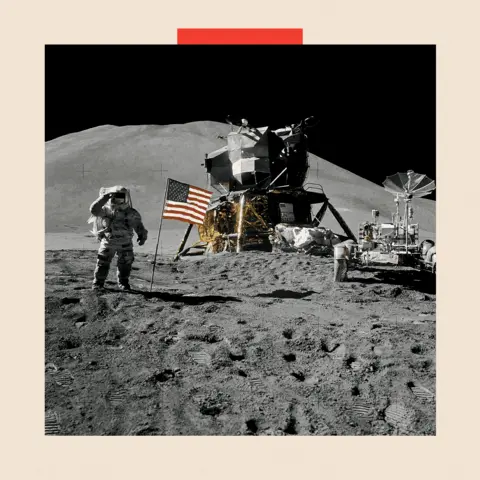

As tensions grew between the US and Soviet Union after World War Two, the concern was that area may turn out to be a navy battleground, so the important thing a part of the treaty was that no nuclear weapons may very well be despatched into area. More than 100 nations signed up.

But this new area age seems completely different to the one again then.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne main change is that modern-day Moon missions will not be simply the initiatives of countries – corporations are competing, too.

In January, a US business mission referred to as Peregrine introduced it was taking human ashes, DNA samples and a sports activities drink, full with branding, to the Moon. A gasoline leak meant it by no means made it there, nevertheless it sparked debate about how delivering this eclectic stock fitted in with the treaty’s precept that exploration ought to profit all humanity.

“We’re starting to just send stuff up there just because we can. There’s no sort of rhyme or reason anymore,” says Michelle Hanlon, an area lawyer and founding father of For All Moonkind, an organisation that seeks to guard the Apollo touchdown websites. “Our Moon is within reach and now we’re starting to abuse it,” she says.

But even if lunar private enterprise is on the increase, nation states still ultimately remain the key players in all this, Sa’id Mosteshar, director of the London Institute of Space Policy and Law, says any company needs to be authorised to go into space by a state, which will be limited by the international treaties.

There’s still a great deal of prestige to be had by joining the elite club of Moon landers. After their successful missions, India and Japan could very much claim to be global space players.

And a nation with a successful space industry can bring a big boost to the economy through jobs, innovation.

But the Moon race offers an even bigger prize: its resources.

While the lunar terrain looks rather barren, it contains minerals, including rare earths, metals like iron and titanium – and helium too, which is used in everything from superconductors to medical equipment.

Estimates for the value of all this vary wildly, from billions to quadrillions. So it’s easy to see why some see the Moon as a place to make lots of money. However, it’s also important to note that this would be a very long-term investment – and the tech needed to extract and return these lunar resources is a some way off.

In 1979, an international treaty declared that no state or organisation could claim to own the resources there. But it wasn’t popular – only 17 countries are party to it, and this does not include any countries who’ve been to the Moon, including the US.

In fact, the US passed a law in 2015 allowing its citizens and industries to extract, use and sell any space material.

“This caused tremendous consternation amongst the international community,” Michelle Hanlon told me. “But slowly, others followed suit with similar national laws.” These included Luxembourg, the UAE, Japan and India.

The resource that could be most in demand is a surprising one: water.

“When the first Moon rocks brought back by the Apollo astronauts were analysed, they were thought to be completely dry,” explains Sara Russell, professor of planetary sciences at the Natural History Museum.

“But then a kind of revolution happened about 10 years ago, and we found out that they’ve got little traces of water in them trapped in phosphate crystals.”

Reuters

ReutersAnd at the Moon’s poles, she says, there’s even more – reserves of water ice are frozen inside permanently shadowed craters.

Future visitors could use the water for drinking, it could be used to generate oxygen and astronauts could even use it to make rocket fuel, by splitting it into hydrogen and oxygen, allowing them to travel from the Moon to Mars and beyond.

The US is now attempting to establish a new set of guiding principles around lunar exploration – and lunar exploitation. The so-called Artemis Accords state that extracting and using resources on the Moon should be done in a way complies with the Treaty for Outer Space, although it says some new rules might be needed.

More than 40 countries have so far signed up to these non-binding agreements, but China is notably absent from the list. And some argue that new rules for lunar exploration shouldn’t be led by an individual nation.

“This really ought to be done through the United Nations because it affects all countries,” Sa’id Mosteshar tells me.

But access to resources could also cause another clash.

While there’s plenty of room on the Moon, areas close to ice-filled craters are the prime lunar real estate. So what happens if everyone wants the same spot for their future base? And once a country has set one up, what’s to stop another nation establishing their base a bit too close?

“I think there’s an interesting analogy to the Antarctic,” says Jill Stuart, a space policy and law researcher at the London School of Economics. “We’ll probably see research bases being set up on the Moon like they are on the continent.”

But specific decisions about a new lunar base, for example whether it covers a few square kilometres or a few hundred, may come down to whoever gets there first.

“There will definitely be a first-mover advantage,” Jill Stuart says.

“So if you can get there first and set up camp, then you can work out the size of your zone of exclusion. It doesn’t mean you own that land, but you can sit on that space.”

Right now, the first settlers are most likely to be either the US or China, bringing a new layer of rivalry to an already tense relationship. And they are likely to set the standard – the rules established by whoever gets there first may end up being the rules that stick over time.

If this all sounds a bit ad hoc, some of the space experts I’ve spoken to think we’re unlikely to see another major international space treaty. The dos and don’ts of lunar exploration are more likely to be figured out with memorandums of understanding or new codes of conduct.

There’s a lot at stake. The Moon is our constant companion, as we watch it wax and wane through its various phases as it glows bright in the sky.

But as this new space race gets under way, we need to start thinking about what sort of place we want it to be – and whether it risks becoming a setting where very Earthly rivalries are played out.

Daily News InDepth is the brand new residence on the web site and app for the very best evaluation and experience from our prime journalists. Under a particular new model, we’ll convey you recent views that problem assumptions, and deep reporting on the largest points that can assist you make sense of a posh world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content material from throughout Daily News Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re beginning small however considering huge, and we need to know what you suppose – you may ship us your suggestions by clicking on the button under.